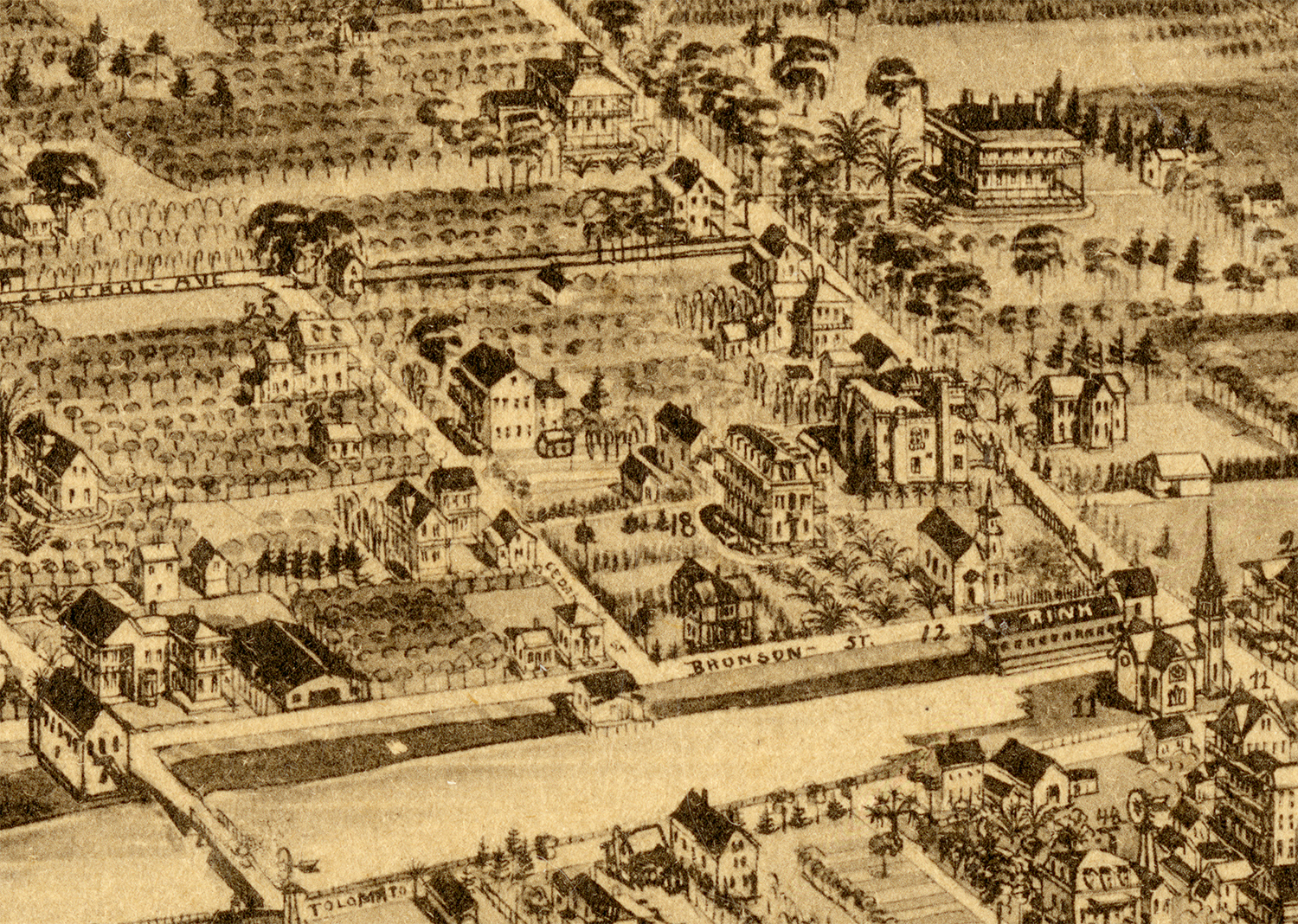

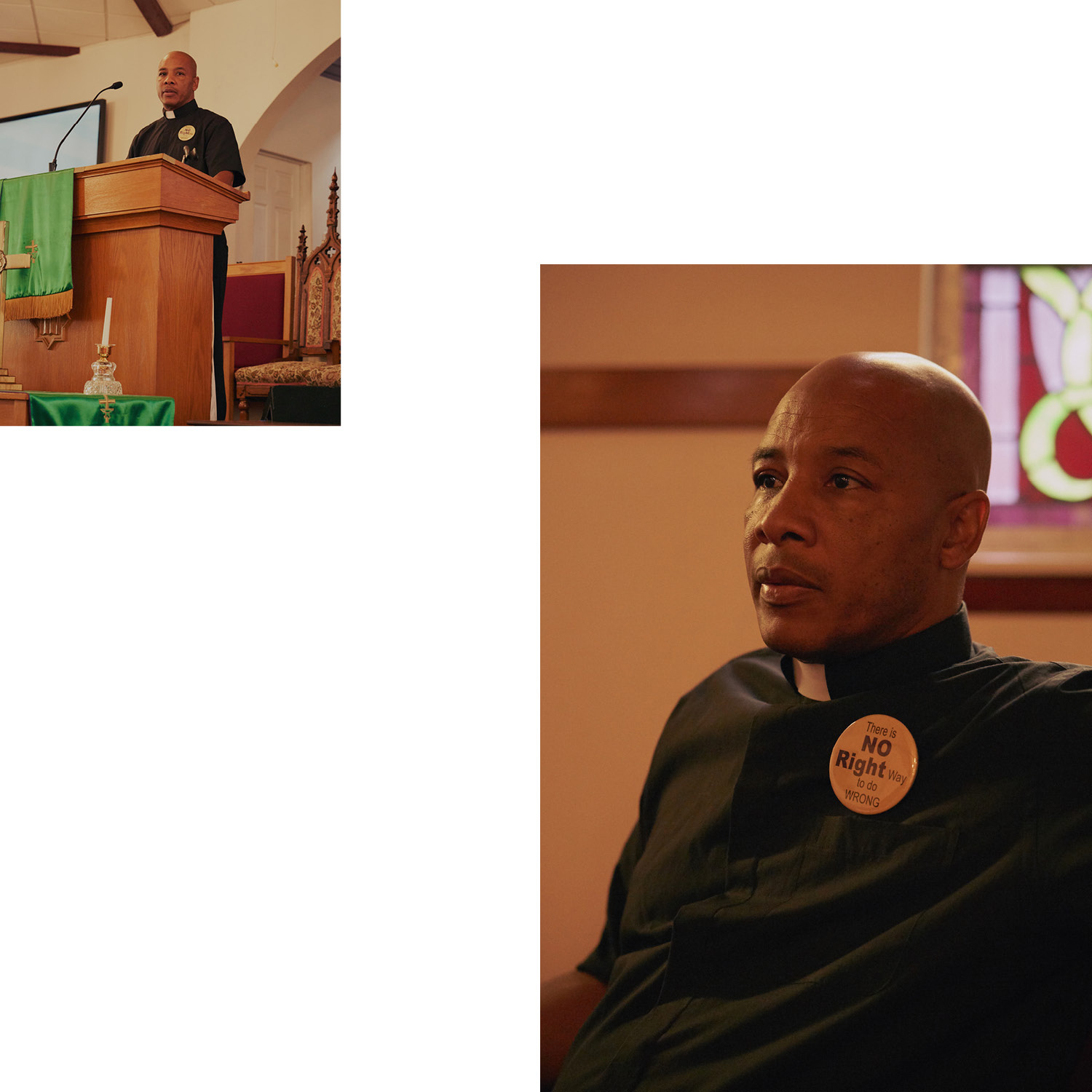

The Reverend — clean-cut in a checked suit and black bowtie, with soft eyes and a bald head — explained that many people knew his church because of its involvement in the Civil Rights movement, citing the presence of MLK and Ralph Abernathy. But Rawls recounted the church’s founding back in 1873, at its original location toward the southern edge of Lincolnville. In 1904, it moved to its “new” location, off what was then called Central Avenue.

Rawls noted that while it figured large as a historic site during the Civil Rights era, he saw its foremost significance as a church founded by freed slaves. “It provided a safe-haven,” he said. “It was a place where people could establish a life for themselves.”

In his ten-years at St. Paul, he has watched the neighborhood change, both from within his congregation and on the street-level. For a long time, nobody paid much mind to Lincolnville’s blemishes — homes that had not received much care or forlorn lots that were scattered throughout the place. But as St. Augustine grew and the downtown area boomed, Lincolnville became prime real-estate. The slow expanse of the City’s tourism industry started making its way South, and then, suddenly, it seemed like people outside the neighborhood cared.

Speculation of what Lincolnville could become has loomed for decades, but in recent years, the promise of this peninsula as the next “thing” has taken root. Gentrification arrived, and the quiet yet violent forces built up over the area like a summer squall. The image of bulldozers that David Nolan had posited were not a wild exaggeration. They were a reality — if a bit more gradual. The displacement in Lincolnville is not readily visible; it has taken place over decades, house by house, block by block, family by family; but it has been acutely felt.

For many pushed up against the wall in Lincolnville, the lack of public programs and resources aimed at helping low-income residents hold onto their properties were seen as a direct corollary to allowing property taxes push people out of their homes. Code enforcement became suffocatingly stringent and ballooning real-estate crippled homeowners. Rawls put it most clearly, “People are losing houses because of taxes.”

As both private and public investments are made in the neighborhood, property values increase and, in turn, the cost of

property taxes follows suit. For some long-term residents and heirs who have been here before Lincolnville was even a twinkle in any entrepreneur’s eye, the recent wave of tax hikes have priced them out.

Many homes in Lincolnville are passed down through generations. With the cost to keep a home in Lincolnville rising steadily, some heirs are forced to make difficult decisions as to what to do with the inherited property. If a home has fallen out of code or is in need of repairs, the problem is even more urgent. “Not everyone has $80,000 in the bank,” Rawls said. Often, these families succumb to the pressure of relentless code enforcement by selling off the house to escape the debt that could otherwise take both the house they’ve inherited and their financial security.

As we walked the neighborhood, Rawls would point to a house, tell a story about the former owners, how they lost it, and what the new owners decided to do. He has watched it happen countless times. Some homes have been rehabbed. Some were razed and rebuilt. Some were modest renovations. Some were multi-million dollar homes. And this was where the rising property taxes came into the fray. Rawls, who is also a licensed but non-practicing realtor, pointed to one home estimated to be worth $500,000. Then he showed me the small home directly behind, which belonged to members of his congregation. “It’s good if you’re trying to sell your home,” he said, “But if you’re trying to stay there, your taxes go up, and you didn’t necessarily ask for that.”

Rawls didn’t believe the neighborhood was a priority for the City prior to gentrification, but he countered that for the slim remainder of black residents still there, gentrification has brought storm drains, adequate sewer lines and even sidewalks. Maybe food and grocery would follow, too, because other than an upscale farm stand, a recently opened breakfast diner/luncheonette, and a small general store, the neighborhood had no place to buy groceries — especially at tenable cost.

In 2007, when Rawls first took his post in St. Augustine, he remembered a corner store up the street where men used to hang out. “They weren’t doing everything on the up and up,” he said, and residents started to complain, particularly the newcomers. “What you saw when you came into the neighborhood were a bunch of black folk hanging out on the corner outside the store,” he said. “They got that fixed up pretty quick.”

“In black neighborhoods, people like hanging out. That’s the culture,” Rawls told me. He pointed to a cedar tree outside a boarded up house where ten years ago, you would see people taking refuge in the shade. Now, those hangouts have disappeared. “You don’t see it anymore,” he told me. “Those are the things they don’t want to see.”

“The reality is that the place belongs to different people,” he added in a somber tone. “We’re trying to do things to slow down the process, but we can’t stop it.” As to talking with the city about the effect gentrification has had on Lincolnville, he said, “They still miss it.”

“They call me everything but a preacher,” Rawls mused of the City and added, “My skin color diminishes my voice in City Hall.” And to be fair, many people on all sides of this story had both criticisms and commendations for the Reverend. Around town, you could find bumper stickers depicting Rawls with devil horns, but residents of Lincolnville saw him as both a failure and savior, sometimes too self-interested to see the bigger picture. And many made sure to note that Rawls did not live in St. Augustine but in Gainesville — 75 miles further west.

When it came to honoring the African American community, Rawls echoed Nolan’s sentiment — it was like pulling teeth to get anything done. “That’s life here in St. Augustine. It is what it is,” he said, laughing.

Of the new faces in Lincolnville though, Rawls told me that their thought pattern was a bit different than the vanguard, and he saw that as promising. That entrenched network of good-ole’ boys and times not forgotten may change with a new order. The question would remain who the change would serve.

Walking back up MLK together, I recognized a flyer on the ground, and showed it to Rawls. It was a corporate real-estate firm’s door-knob query aimed at the fire-sale of homes. He looked it over and mused, “Offer them some quarters for their home and hope they jump.”

Further up the road, we peered over a tall hedge, and Rawls greeted a guy tending to a garden as “Boss Man.” They quickly caught up and Rawls told him, “If you need to come talk to me, come talk to me. I don’t want you to lose that,” as he looked up towards the two-story Victorian home.

Boss Man replied, “I ain’t trying to lose it.”

“If you see stuff getting out of hand, come talk to me.”

“Well, it’s a little out of hand, but we’ll talk.”

Rawls gave me the backstory: The owner was inundated with back taxes for five months now, but he hadn’t come to see Rawls yet. The homeowner had been pouring money into maintaining and keeping the house up to code, and now the lien placed on his home by the City had become insurmountable.

Just across the street, Rawls pointed out the home of the Jenkins, who “were pillars in this community.” Now, since the family had passed on and the heirs were living elsewhere, he wasn’t sure what would happen to the property. “Everybody has the right to sell,” he offered, but he made a distinction between the natural process of attrition as compared to the systemic pressures propagated by the city — under questionably nefarious intention.

It seemed clear that there was a lien on Lincolnville, and the longtime residents felt like their heritage was up for sale.

Church bells rang overhead as we said our goodbyes, and the weather broke for a moment. We set down our umbrellas, and Rawls told me why he hadn’t given up on the town. “As strong as that spirit is in St. Augustine,” he said, referring to the movement to reframe Lincolnville as something shiny and new, “there is another spirit here that speaks of our ancestors and our rich history.”

“I hear those voices, too,” he said.